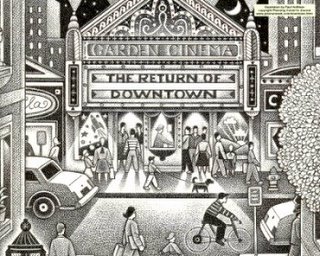

Gone to strip malls every one? To some extent, yes. Malls, strip malls, and an almost total addiction to the automobile have contributed to the decline and, in some communities, the near demise of what was once "downtown."

Gone to strip malls every one? To some extent, yes. Malls, strip malls, and an almost total addiction to the automobile have contributed to the decline and, in some communities, the near demise of what was once "downtown."From mega-mall to strip mall, the Mom and Pop store has been supplanted by the Big Box store, with "Main Street" left about as deserted as the streets of Hadleyville at high noon.

On Long Island, "if you can't drive there, you don't go there," subsumes any thought of "walking" -- to get a newspaper, to buy a quart of milk, to go to church or to school.

And when one hamlet streams indistinguishably into another -- an Elmont ebbs into a Franklin Square which flows into a West Hempstead -- there is not only a loss of that physical sense of community, but, more than this, that visceral or emotional/psychological sense of community so necessary in the life and livelihood of any town.

Suddenly, we are no longer Elmontonians or Lynbrookers, priding ourselves on the look, the feel, the essence of our own local fabric. We become part of a bland, homogenized gruel that looks only at the whole, without noticing, or even so much as acknowledging, the significance of its parts.

True, the "whole" -- as in "big picture" -- is crucial to a thriving community scene, as is the holistic approach to a body's well-being. Still, when the brain ignores the heart, community misses a beat, at best, and, over time, flat-lines into oblivion.

In Anything But Mexican, Rodolfo Acuna chronicles the history of the Chicano population in Los Angeles. While the accounts and struggles of Mexican-Americans in the city of angels may seem far removed from the efforts to rekindle the spirit of community in Valley Stream, the analogies, if just slightly beneath the surface, are most glaring.

Loss of identity. Loss of self. A feeling of having been disenfranchised, removed from control over our surroundings and without access to the powers that, for better or worse, can, and too often, in directions untoward, do exert control.

Without a sense of community, and a sense of their history as a community, people become vulnerable to the plans and whims of the dominant groups, which can not only displace them but control them in other ways as well. There is for example, very little preservation of anything in Los Angeles that has Native American or Mexican roots, with the history of these groups submerged by the presence of other folk. The resulting lack of local history and connectedness has the effect of alienating Chicanos and Native Americans, of discouraging development of a united community. When either group attempts to reconstruct history and regain lost space, the dominant society is offended and claims that the Mexican or Native American is encroaching on its past.

This erasure has devastating consequences: an ethnic group unable to define its past is unable to take pride in its accomplishments, learn from past mistakes or assess its current situation. History is more than just an esoteric search for facts; it involves a living community and its common memory. Anything But Mexican, 1996, pp. 19-20.

In a very real, and sometimes frightening way, most Long Islanders, residing in often ill-defined communities with makeshift and myriad boundaries, are without that same or shockingly similar sense of community. We are reduced to tending, if only by oversight, to unincorporated places, bounded by overlapping and incongruous school districts, fire districts, water districts, library districts, and so on down those artificial lines that divide and separate.

We are "encouraged" to participate -- from Town Board meetings to neighborhood forums -- yet fail to discern the connectivity between our own perception of involvement and the ceding of control to the "whim" of bureaucracy that results from our inattentiveness to civic duty.

Acuna was right. Our sense of place "involves a living community and its common memory." Without that sense of community, we become vulnerable, displaced, unable to preserve the past or to envision the future.

In A Sense of Where We Are, Adam Gordon, then a senior at Yale University's Branford College, wrote:

"Apathy is frozen violence," an Australian farmer told my father seven years ago during a conversation about American politics. The past year has taught me something about why Americans are so apathetic. It's because we've lost a sense of community. In order to reclaim that sense of community, we must all shake ourselves out of our apathy and work to shape the future of our communities and our world.

With property taxes through the roof, illegal basement apartments in every other house, school budgets in the stratosphere, and the plethora of ills that plague our communities, one would think there'd be sufficient cause to "shake ourselves out of our apathy." Apparently not.

"But somewhere beyond the mask of apathy is, indeed, frozen violence," said Gordon, in words well-worn beyond the wisdom of his young years. "We wish that we could be part of something bigger. We yearn for the communities that our grandparents grew up in, where everyone knew each other and looked out for each other... But we have frozen these feelings because we do not think that we have the ability to change such large forces."

Zygmunt Bauman, in Seeking Safety in an Insecure World, argued that we need to work to "gain control over the conditions under which we struggle with the challenges of life." For most of us "such control can be gained only collectively."

It is both fact and basic truth that such control is ours -- individually and collectively -- frozen right there alongside that pent up violence, awaiting its release in the hope that we, as community's guardians, might harness it.

We could go on, chapter and verse, on "how to" reclaim that lost sense of community. In coming blogspots, we no doubt will. As introduction to Chapter One, however, we will simply offer homage to Yale's Adam Gordon, citing the sentinal language of his closing paragraphs as prelude to community's resurgence:

...To make our communities places where people interact with, and care about, their neighbors. To make our communities places where church homecomings, community festivals and neighborhood hardware stores are familiar parts of the landscape.

The first step, however, is to unfreeze the anger that we have pretended does not exist in our apathy. All that apathy does is keep the status quo that our frozen violence is directed against going. So get involved, in your hometown, in New Haven, in whatever city you move to after graduation. That does not mean that you necessarily should go out and march on Washington tomorrow. Getting involved in a local sports league, religious institution or political organization is as important as fighting for social justice. The basic message is the same: We're reclaiming control over our communities. Our streets. Our cities. Our world.

- - -

Click HERE for an overview of Community Building: Strengthening The Sense Of Community

- - -

Is there a "sense of community" -- the "belonging" to "part of something" that empowers residents -- in your hometown? At The Community Alliance, we'd like to know. Post a comment to this blog, write a Guest Blog for publication, or simply e-mail us at info@thecommunityalliance.org with your thoughts and ideas.

No comments:

Post a Comment